To expand on the topic of Hair-ism, I had the privilege of speaking to Joseph Taylor a 22-year-old barber working for himself at his Embassy Hair Studios in Melbourne, St Kilda. Jo describes facing the lack of training he received in the cutting of African hair types after finishing his barbering apprenticeship. We also chat about his personal experiences as a child that eventually led him to a career as a barber, and his views on the need for more hair studios specialising in the cutting and styling of afro hair in Australia. Jo emigrated to Australia from the UK and he talks about the differences in hair culture being of Jamaican/English heritage now living in Melbourne.

HAIR-ISM

The fuss over follicles.

The western beauty standard

My hair is curly, not kinky tight curls but not straight. Being of Southern African heritage with mixed DNA meant my hair texture lay somewhere between Africa, England, and Germany. My father’s hair was always chemically straightened. Chemically straightening his hair was my father’s hair ritual. His hair regime defined much of my morning memories of him. I was fascinated with the chemistry of it all, the smells, the application, the blow wave finish. The combining of creams and solutions that once applied would magically transform my father into the straight-haired default he desired. A default I never comprehended fully as a child.

Photos of my father’s hair in South Africa was big and bushy. Something closer to a seventy’s afro. I love those images of him, he seemed so much cooler. All that was missing was the roller skates. Now in my forties I better understand his desire for straight hair. It was my father’s way of living up to a European beauty standard perpetuated through a need to assimilate into a new culture that was predominantly white. More importantly he understood the assignment. My father’s cultural assimilation into Australian culture was vital in applying for jobs as an educator in religious schools. His intersectionality fell across appeasing negative stereotypes of black textured hair in eighties Australia, and the expectations of vocational standards of acceptable appearance through that time.

As a child I never saw the societal implications of having curly or afro hair until I started school myself. I was different to most kids I was brown, short, curly haired with a funny accent. I secretly hated it. I’d be taunted with comments of ‘jex head’ ‘bah bah black sheep’ ‘mop head’. Slurs I’d laugh off that were usually combined with racial slurs at the colour of my skin. I was a ‘Boong’, ‘Jungle bunny’, ‘Giggaboo’ a ‘Rock Ape’ to name a few. A time when ‘who was it’ in games of tag were defined by catching a nigger by the toe. ‘

“Stick and stones may break your bones, but names will ever me”

This was the mantra to racism my parents taught us as kids. No matter how many times ‘mates’ would wipe my skin telling me I was ‘shit-stained’ my colour never rubbed off and my hair never changed. The names didn’t hurt, and I defended myself against the stick and stones however I knew I was something different to the norm.

Physical appearance bias permeates culture whether it be attractiveness, weight, ageism, height, even red coloured hair. We all can fall victim to appearance bias in some way. Hair plays a big role in everyone’s identity. Appearance bias however is different to ‘Hair-ism’ confronted by many black and brown people. This is especially true of black woman whose hair plays a substantial role in their identity.

BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of colour) communities are affected by expectations of appearance and beauty that are baked into the colonialised mentality of a default white grooming standard. This extension of white superiority harks back to the era of slavery, where captured Africans embarking on ships had their heads shaved. Black Americans, Africans and Afro-Latinx people around the world adhere to a straight-haired default in their daily ritual of grooming. Relaxing kinky hair meant using dangerous concoctions. Many products today proving dangerous to the health of those using them. Many chemicals now are linked to hormone disruption and cancers.

These standards are not limited only to hair, but also skin colour. Skin whitening lotions and treatments have been around for many years and popular in many Asian countries. Indigenous communities, working in rural areas are usually darker skinned and are seen as lower class. These white skinned beauty standards are also being challenged in the fashion and beauty industry for its limited representation of black and brown skin.

So, what is hair-ism?

Simply put Hair-ism is the discrimination of people with Afro-textured hair. A style of hair that is culturally unique to certain communities globally. This form of discrimination can have detrimental effects on employment, schooling, and freedom of expression. Afro textured hair has been seen as untidy, unkept, unprofessional and unclean. Hair-ism is a social injustice that still effects BIPOC children and adults today. Andrew Johnson, a wrestling student in America was forced to shear off his dreadlocks at a school wrestling event in front of the whole stadium. This action caused a lot of controversy, shining a light on hair discrimination. As a result the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association (NJSIAA) made changes to the rules to make sure situations like Andrew’s won’t happen again.

How hair-ism is related to racism

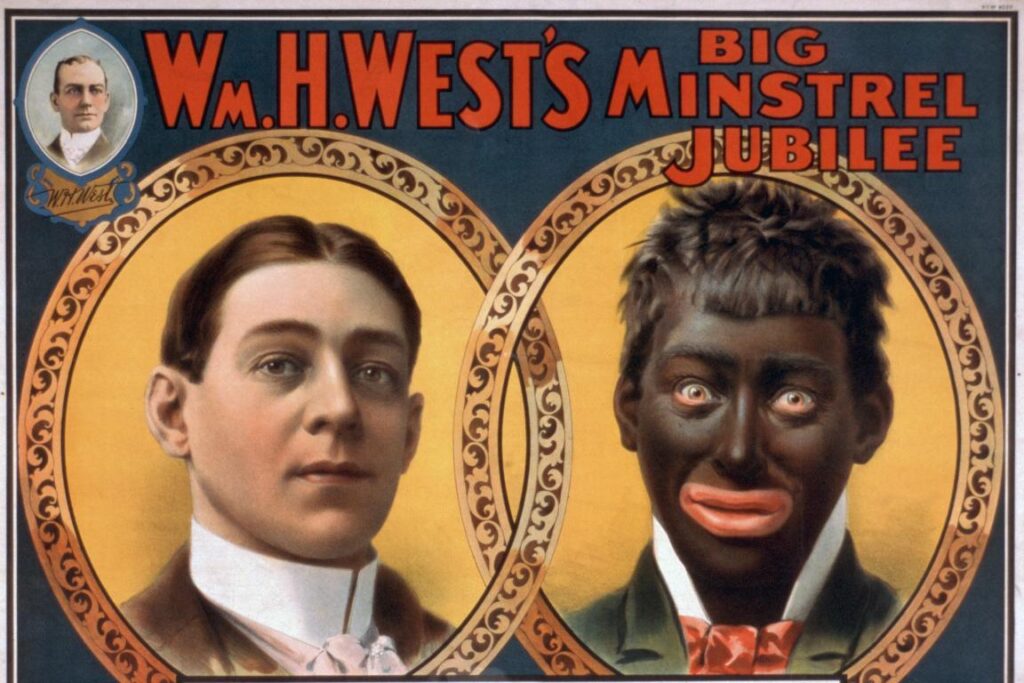

Effects of characteristics that differ from a European standard are directly related to racism and colonialism. The stereotypes of black people being uneducated, lazy, dirty, and dangerous were propagated by working class white people feeling disenfranchised politically, socially and economically. Minstrel shows, Gollywogs and racist caricatures were extreme exaggerations of ‘Blackness’ and a form of amusement to a middle-class white community’s desire for cultural elitistism. These ideas of beauty and appearance still pervade many cultures the world over and have direct corelations to job opportunities, education, identity and social perceptions. The advent of mass emigration in the 20th and 21st centuries has only exacerbated the problems of hair-ism.

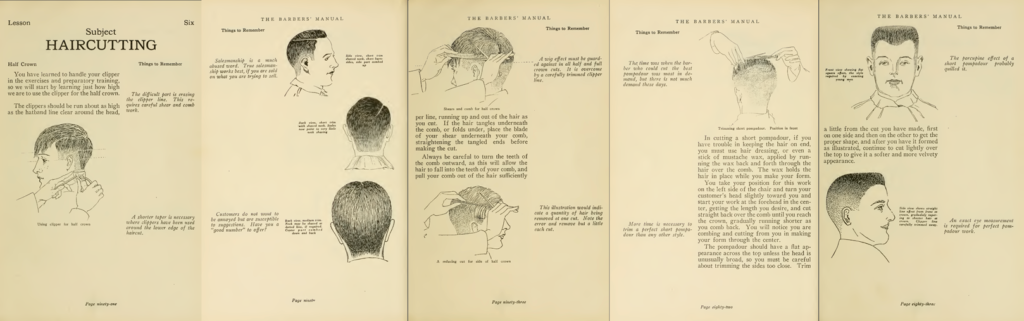

Australia in the last decade has seen an increase of African migration into predominantly white cultures. As we see with most emigration experiences, is the exposure to new cultures, new cuisines, festivals, and different looking neighbours. Barbers in Australia have been around since the early 1900s however cutting textured hair was never a real consideration for most barbershops in Australia. The skill of becoming a barber in Australia was never one of learning to cut black people’s hair. Due to the mainly a cultural dominance of white Australian communities over bigotry or racism. However, the training around becoming a barber still has not met with the change in the multicultural societies we see today.

A Barbers view of Hair-ism

Jo Mayka is a barber in Melbourne who recounts his experience of barbering as a mix race person of Jamaican and English heritage with kinky hair. When asked if he thought textured hair is well represented in Melbourne barber shops Joe responded by saying.

‘I assume textured hair representation is meniscal in terms of the demographic of Afro haired people in the community.’

‘Black hair is also braiding, deadlocking done naturally without chemicals, perming solutions or beeswax. It’s more than just the scissors, combs, and water. These are specialist skills that I feel should be taught or at least an option included in the training of all barbers and hairdressers’

Who taught you how to cut black hair?

‘No one taught me to cut black hair. I taught myself through the haircuts I gave myself, and YouTube’ He laughs.

‘When I did my training, we never covered cutting textured or tight curls.’

Do you feel more representation is occurring in Melbourne barbers?

‘I find a lot of the changes being made now in the industry are more performative. At the end of the day most barbers are about people in the chairs than diversity and inclusion; especially if it means more training and expense.’

The Hairy Conclusion

Barbershops are important cultural meeting places for many black Americans. It is a space for grooming and psychological developmental. Black woman’s hair maintenance is usually a skill passed down from mother to daughter. It’s family bonding or a safe space for character development. Hair texture and hairstyles is one idea of identity, widening the limited view of western beauty ideals means re-shaping social inclusion. By removing the filter of long held racist stereotypes permeated into modern day culture we swop judgements of appearance to content of character. Actions are being taken locally in Australia and around the world to combat hair discrimination. Musician JamarzOnMarz is calling on the NSW government to change school uniform policies that discriminate against natural Afro hairstyles. Globally too, we see the Crown act in America taking shape in many states changing policy to protect people against hair discriminations nation-wide. BIPOC people have a stake in what beauty standards they adhere to derived from the natural quality of their hair. These forms of discrimination are sometimes conscious and more than often unconscious perceptions that have been passed down from another era that still seeps into everyday life. It may not seem that important but when you’re dealing with people’s opportunities for work, education and social acceptance it’s clear that change has to happen

Table of Contents

On Key